|

| Yura Lee and Kevin Fitz-Gerald at Rolling Hills United Methodist Church. |

REVIEW

Yura Lee and Kevin Fitz-Gerald, Second Sundays at Two, Rolling Hills United Methodist Church

DAVID J BROWN

April’s recital in Classical Crossroads’ “Second Sundays at Two” 2021-22 season in the South Bay was, like the previous concert, recorded—as had been intended for the whole season before the Omicron Covid variant emerged—before a small invited audience, duly Covid-vetted and masked, for future YouTube posting: on the due date of Sunday, April 10 in the case of this recital of violin sonatas by Beethoven and Fauré.

The views of Beethoven as a fist-shaking titan while of Fauré as a kind of musical epitome of Proustian introspection are both gross over-simplifications, and indeed it would be difficult to find in the output of each composer two works that more thoroughly refute these images than Beethoven’s Sonata for Piano and Violin No. 10 in G major Op. 96 and Fauré’s Violin Sonata No. 1 in A major Op. 13 (interestingly, the title on Fauré's manuscript still gives primacy to the piano over the violin, as was Beethoven's custom).

Beethoven’s final violin sonata was composed in 1812 on the cusp of what are generally regarded as his “middle” and “late” periods of composition, and a full nine years after its immediate predecessor, the enormous “Kreutzer” sonata. The Op. 96 sonata has little of the “Kreutzer”'s spacious grandeur, instead predicating its (mostly) amiable character, at least in the outer movements, on the imitative birdsong-like trills, first on solo violin, then on piano, with which the first movement opens.

Which is not to say that the work does not have its own considerable strengths, all of which were fully brought to the fore in the performance by the Korean-American violinist Yura Lee and Canadian pianist Kevin Fitz-Gerald that formed the first half of this recital. Their account of the expansive and lyrically pastoral Allegro moderato first movement was made more so by their inclusion of the relatively long exposition repeat.

|

| Beethoven in 1812: digital sculpture by Hadi Karimi. |

To my ears this sonata, though in four distinctly labeled movements, seemed more than usual to fall into three roughly equal and highly contrasted parts. This was due not only to the built-in factor that its relatively brief slow movement is linked by an attacca to the (even for Beethoven) exceptionally concise scherzo and trio, but also to the players’ trenchant and serious, though not particularly slow, treatment of the Adagio espressivo and their immediate and gritty attack on the scherzo, so that this movement seemed more like a frowning coda to its predecessor than an independent entity.

All this was in marked contrast to the genial and mostly relaxed first movement, so that when the Poco allegretto finale began— with Ms. Lee and Mr. Fitz-Gerald giving the opening tune of its (unmarked) theme-and-variations structure all the dancing insouciance it needs—the mood seemed very much an all-is-really-right-with-the-world callback after the seriousness of the linked middle two movements. These two marvelous players did not, however, fail to give full measure to the gruff brilliance and quicksilver expressive changes with which Beethoven swings from variation to variation in the finale.

Their performance of Gabriel Fauré’s first violin sonata was, if anything, even finer. Though it’s worth remembering that Beethoven was still only 42 when he reached the relatively late stage in his career marked by his last work in this form, and that Fauré was already 30 when he came to his first, his sonata nonetheless marks the opening and decisive stage in his long and auspicious career as a composer of chamber music.

|

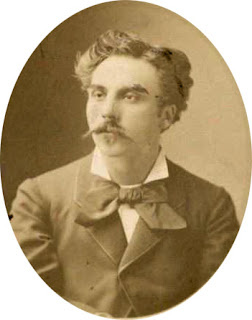

| Fauré in 1875, the year he began his Violin Sonata No. 1. |

Their performance of the movement, and indeed of its three successors (the young(ish) Fauré adheres the eternal verities of slow movement/scherzo & trio/ fast finale), was full of light and shade and nuance, rising to passionate intensity and an unerring sense of where to place climactic moments with the utmost effect.

This was nowhere more the case than at the passage towards the end of the first-movement development when Fauré’s unrelentingly high-lying violin line (which, however, nowhere seemed to faze Ms. Lee), crescendos over three measures from a thread of ppp tone above long-held widespread chords on the piano to a sforzando peak—wonderful stuff, as you will be able to hear for yourself when this recital goes live on Sunday, April 10.

---ooo---

Rolling Hills United Methodist Church, Rolling Hills Estates, Sunday, April 10, 2022, 2.00 p.m. (recorded Sunday, March 27).

Images: The performers: Courtesy Classical Crossroads; Beethoven: Hadi Karimi; Fauré: Wikimedia Commons.

If you found this review to be useful, interesting, or informative, please feel free to Buy Me A Coffee!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.