|

| The Thies Consort at LAHC Miller Recital Hall: l-r Jessica Guideri, Robert Thies, John Walz. |

The Thies Consort, South Bay Chamber Music Society, Miller Recital Hall, Los Angeles Harbor College

Gupta/Lewis/Kaufman trio, Mason Home Concert

DAVID J BROWN

Maybe it’s just my reaction (though I don’t think it is), but the performances we’ve been enjoying since the resumption of live concerts here in the LA area seem by and large to have been imbued with a special charge—an extra vigor and/or sense of commitment and/or enthusiasm; perhaps even more, a renewed infusion of vital necessity—and by that not-so-mysterious osmosis between performer and listener, this seems to have been mirrored in audience reactions.

|

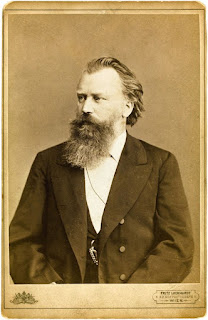

| Brahms in 1882, the year he completed his Piano Trio No. 2. |

Two concerts from the last season before the pandemic of the (surely) unique chamber music series that LA composer Todd Mason presents in his Mar Vista home have previously been reviewed on LA Opus (here and here) and as my colleague John Stodder will be reviewing the latest recital in detail, there’s no need for more than a brief note about it here.

That “special charge” was fully in evidence throughout the passionately driven performances by Geneva Lewis (violin), Mike Kaufman (cello), and Marisa Gupta (piano)—amazingly, they apparently do not play together regularly as a trio—of two works by Robert Schumann, and then after the interval for refreshments, the Brahms.

Schumann’s 6 Studien in kanonischer Form Op. 56 were originally written for the pedal piano, but sounded entirely idiomatic in this transcription for piano trio, while the intensity of Ms. Lewis’s playing in Schumann’s three-movement Violin Sonata No. 1 in A minor Op. 105 made the piece even more darkly concentrated than usual.

|

| Robert Thies. |

While no less filled with that “special charge” of vitality and urgent communicativeness, in this hall’s ampler acoustic their performance of the Brahms had seemed more warmly homogeneous and perhaps more reflective; but, though it seems odd to say it of a mature work by one of the greatest composers who ever lived, the piece seemed somewhat constrained and diminished by comparison with the towering masterpiece that had preceded it before the interval.

|

| Dvořák in 1882, the year before he completed his Piano Trio No. 3. |

Robert Thies opened with a characteristically insightful reflection on the mentee/mentor relationship between Dvořák and Brahms, eight years his senior, who from 1874 onwards was profoundly influential in securing both material reward and widespread recognition for the younger composer’s genius. This artistic and public recognition in turn seems to have strengthened the confidence with which Dvořák drew together the singularly Czech aspects of his art with an increased mastery of classical forms.

|

| Jessica Guideri. |

But Dvořák’s Piano Trio No. 3 in F minor, Op. 65, B. 130, composed in 1883 in the full focus of Brahms-enabled celebrity, far outshines its two predecessors and one successor in scale, depth, and seriousness of utterance. As if striving to justify that new fame, he rose to achieve one of his very greatest works, which arguably stands in relation to the remainder of his chamber music output as his two greatest symphonies, Nos. 6 in D major, Op. 60 (1880) and 7 in D minor, Op. 70 (1884-85) loom amongst his orchestral works.

|

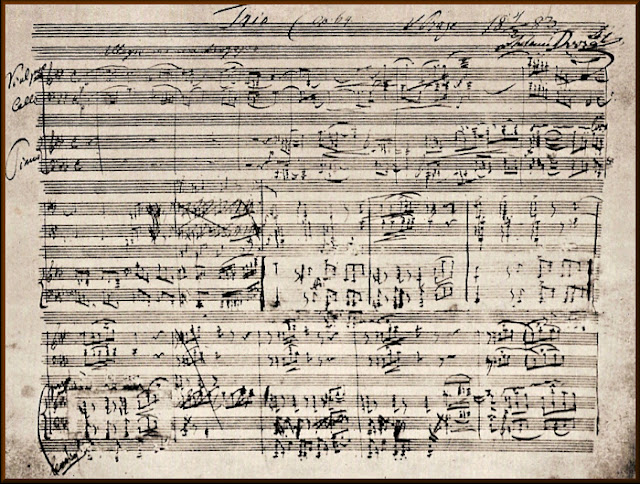

| The first page of the manuscript of Dvořák's Piano Trio No. 3. |

Chronologically between the two, and with an opus number symbolically mid-way between theirs, Dvořák’s Piano Trio No. 3 manages to combine the architectural scale of the former symphony with the dramatic intensity of the latter. In the hands of The Thies Consort, the first movement Allegro ma non troppo in particular attained heights of steely grandeur, with a vibrant attack masking the exceptional spaciousness of their account, which stretched to a full quarter-hour (and with no marked repeat of its exposition to muddy, due to whether it is observed or not, the durational waters).

|

| John Walz. |

In the preceding Allegretto grazioso scherzo, The Thies Consort nimbly negotiated the opening's tricky cross-rhythms—perfectly synchronized dancing triplets from Ms. Guidieri's violin and Mr. Walz's cello against vehemently articulated duple meter from Mr. Thies—and then in the finale they encompassed both a no-holds-barred attack on the obsessive dotted rhythms of the main Allegro con brio material and the brief tendernesses of the tranquillo interludes that punctuate it.

In the astonishing coda, the alternation between these polar opposite moods becomes ever more abrupt and extreme, as if the music threatens to rip itself apart irrevocably, but somehow Dvořák manages to pull the movement together to an emphatically unanimous conclusion—all faithfully rendered by Robert Thies and his colleagues. After that, anything else would have been an anti-climax.

---ooo---

South Bay Chamber Music Society, Los Angeles Harbor College, 8 p.m., Friday, December 3, 2021.

Mason Home Concert, Mar Vista, 6 p.m., Saturday, December 4, 2021.

Images: The Thies Consort: David J Brown; Brahms and Dvořák: Wikimedia Commons; Robert Thies: artist website; Jessica Guideri: courtesy LA Chamber Orchestra; John Walz: Idyllwild Arts.

If you found this review to be useful, interesting, or informative, please feel free to Buy Me A Coffee!

No comments:

Post a Comment