|

| Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra at the Segerstrom Concert Hall on October 11, 2022. |

REVIEW

City of Birmingham Symphony at the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall, Costa Mesa

DAVID J BROWN

It can be salutary to hear live for the first time in a long while a work that one thought one knew well from recordings. For me, this was certainly the case with the first item in the artfully conceived and brilliantly executed program, introduced by the Philharmonic Society of Orange County's President and Artistic Director, Tommy Phillips, that the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and its former Music Director and current Principal Guest Conductor, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, brought to the Segerstrom Concert Hall under the auspices of the PSOC, in the first concert of the Society’s 2022-2023 season.

|

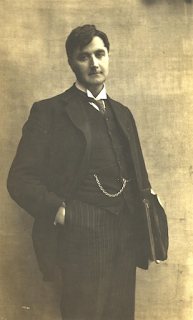

| Ralph Vaughan Williams, c.1910. |

But this view vanished rapidly as the sheer beauty of the CBSO strings and their responsiveness to her animated direction took hold. RVW scored the work for solo string quartet and double string orchestra (the second comprising pairs each of first and second violins, violas, cellos, and a single double-bass), but with no particular stipulation in the score about spatial separation of the three bodies. In this instance the main group of players was spread across almost the entire width of the performing area, with the quartet in their normal section-principal seats at the front.

|

| Gloucester Cathedral, location of the first performance of the Tallis Fantasia in 1910. |

It could easily be argued that the well-known Tallis Fantasia was an “easy” way to honor its great composer on his anniversary, and that something rarer from his voluminous output would have been welcome. This performance, however—lithe, sensitive and with the subtlest gradations of timbre and dynamic (and, I suspect, following RVW’s metronome markings closely to come in at just on 15 minutes, and thus notably swifter than many modern accounts)—was an impressive augury of what was to follow.

Masterpiece though it is, Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85, composed in 1919, can also be charged with over-familiarity in the face of the neglect, at least here in the US, of most of his major works, but as with the Vaughan Williams, the performance that followed by the young British cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason stilled any such reaction. This gifted player is one of no less than seven siblings who have become something of a musical sensation in the UK, with many live performances together and separately, and in particular, domestic YouTube recordings made during the Covid lockdown.

Mr. Kanneh-Mason’s recent commercial recording of the Elgar concerto has received a bit of a sniffy backlash from domestic UK critics, but there was nothing to take issue with at the Segerstrom, where his partnership with the CBSO and Ms. Gražinytė-Tyla, following an acclaimed performance at the 2019 London Proms, had a sensitivity and homogeneity that bespoke deep mutual regard and esteem for the work.

|

| Sheku Kanneh-Mason with the CBSO under Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla plays Elgar's Cello Concerto in the Segerstrom Concert Hall. |

|

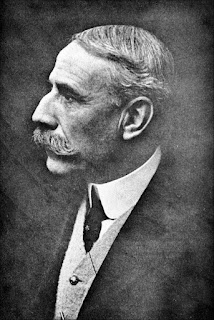

| Edward Elgar in 1917, shortly before he began work on his three chamber music masterpieces and the Cello Concerto. |

Mr. Kanneh-Mason returned for an encore, and fittingly it was not some gasp-inducing piece of technical wizardry but his own arrangement, delivered with rapt focus, of J. S. Bach’s song Komm, süßer Tod, komm selge Ruh (Come, sweet death, come, blessed rest) BWV 478, the solo line joined in its later stages first by one and then a second pair of his colleagues from the CBSO cello section. This, Bach’s contribution to a 1736 collection published by one Georg Schemelli, might have been taken as a call-back to the first item, given that the Tallis original from which RVW took his theme was a tune comparably included in a Psalter, some 169 years earlier.

After the interval, in the words of Monty Python, “something completely different.” Amongst the legion of gifted composers who, for all sorts of reasons, have not made it into the mainstream of classical music awareness and concert repertoire, the Polish/Russian/Jewish Mieczysław Weinberg (1919–1996)—close friend of Dmitri Shostakovich and almost the fatal victim of a late Stalinist purge for “Jewish bourgeois nationalism”—is surely one of the most significant and deserving of a permanent place in that repertoire.

|

| Mieczysław Weinberg. |

Now here it was again, as a staple item in the orchestra’s current US tour, and what a discovery! Sharing the unsettling “anything could happen” quality of some Shostakovich, this wild 11-minute ride swerves between solos from woodwind and percussion, sometimes impassioned, sometimes mournful, and sudden eruptions first from the strings and later the full orchestra. Variously motoric, rhapsodic, exultant, and exhausted, it compelled the ear and made one wish there was more. (The depth of Ms. Gražinytė-Tyla’s commitment to Weinberg, and the scale of his achievement, can perhaps best be demonstrated by her recording of his magisterial Symphony No. 21 Op. 152 "Kaddish" available to be heard here on YouTube, in which she not only conducts the CBSO but also sings the wordless soprano solo in the sixth and final section.)

|

| Debussy on the beach at Eastbourne, Sussex, England, where he corrected the proofs for La Mer's publication in 1905. |

The clarity of the Segerstrom acoustic, of course, aided and abetted the performance’s laying bare so much of the intricacies of Debussy’s marvelous score, and if this account tended to emphasize La Mer’s status as one of the orchestral showpieces of the early 20th century (a “rite of spring-tide” perhaps) rather than its “impressionistic” qualities—a term which in any case Debussy himself despised—it was none the worse for that, and was justifiably cheered to the Segerstrom’s glowing, curved rafters.

|

| Thomas Adès. |

As well as being beautiful in itself, the inclusion of O Albion was the perfect link back to the concert’s opening, Adès’ nostalgic, sighing textures joining hands not only with those of Vaughan Williams writing his Fantasia in 1910 and Master Tallis penning the original hymn-tune in 1567, but opening out into a wider, indefinable, almost mystical “Englishness” that embraced them all. A memorable concert indeed.

---ooo---

City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, presented by the Philharmonic Society of Orange County, Renée & Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall, Costa Mesa, Tuesday, October 11, 2022, 8 p.m.

Images: The performance: Drew A. Kelley; Vaughan Williams, Gloucester Cathedral, Elgar, Weinberg, Debussy: Wikimedia Commons; Adés: Prospect Magazine.