|

| LACO Music Director Jaime Martín and guest violinist Gil Shaham perform Dvořák’s Violin Concerto in A minor at the Ambassador Auditorium in Pasadena. |

REVIEW

But in fact it was a festive and special occasion. To celebrate the 200th anniversary of diplomatic and cultural relations between Mexico and the United States, the Mexican Consulate was honoring Juan Pablo Contreras (b.1987), a participant in LACO’s Sound Investment program for commissioning new works, for his "significant binational artistic contributions," and to crown the occasion, the LACO and its Music Director Jaime Martín gave the premiere of his latest work, Lucha Libre!

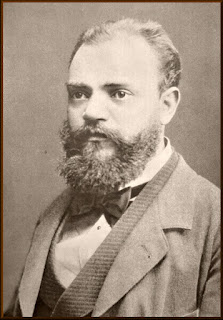

From this relatively recent Mexican cultural phenomenon, the focus of the remainder of the concert moved half-way across the globe to central Europe and its much older and diverse folk-music traditions. In his major symphonic-scaled works, Antonin Dvořák was no less influenced by Czech folk song and dance than the smaller pieces that directly quoted or reworked this heritage, and his Violin Concerto in A minor Op. 53 B.96/108 is no exception.

This set the tone for the whole performance, replete with a freshness and joy as of new discovery on the part of all concerned, visible constantly in the delighted expressions and body language of both Shaham and Martín, the former’s slight form often swaying close in response to the upper strings, while Martín energetically pointed orchestral detail after detail. Apparently one of them said to the other in rehearsal “Let’s dance,” and it was easy to believe!

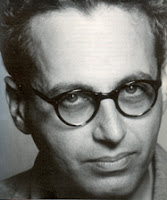

After the interval, and following touching tributes (right) to retiring violinist Julie Gigante from Concertmaster Margaret Batjer as well as the conductor, the second half was devoted entirely to further exploration of that central European folk-music tradition through three works that explicitly celebrated it by three 20th century masters, the Romanian-born György Ligeti (1923-2006) and the Hungarians Béla Bartók (1881-1945) and Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967).

Any concerns that all the brief folk-dance movements that make up these works (no less than 15 of them across the three pieces) might get a bit samey were rapidly dispelled by the strong contrasts between them.

Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Ambassador Auditorium, Pasadena

DAVID J BROWN

Any mid-December concert that includes no specific holiday/Christmas-themed items, and in which the most well-known work is a 19th century violin concerto that’s not one of the Big Three Bs—Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch—deserves all the support it can get, and it was most gratifying to see, after a day of rain and on a (for southern California!) very chilly evening, a near-capacity audience in Pasadena’s Ambassador Auditorium for the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra’s final concert of 2022.

|

| l-r: Martinez Ciana, Deputy Consul General Minister, Mexican Consulate of Los Angeles; composer Juan Pablo Contreras; Cynthia Prida, Cultural Attaché, Mexican Consulate of Los Angeles; Jaime Martín. |

In an engaging chat before the performance, Sr. Contreras said that the inspiration for the piece had lain in his appreciation of teamwork, both between members of the symphony orchestra and amongst the tag-teams of combatants in the iconic Mexican masked wrestling that gives the work its title. To celebrate this in his Lucha Libre!, therefore, he pits two groups of solo players against each other—three rudos (villains) versus three técnicos (heroes).

Alongside each soloist was a luchador mask (left), designed by Contreras’ wife Marisa, to identify them: the rudos were Don Diavlo (“The Devil”—Andrew Shulman, principal cello), Astro Tapatio (“The Star of Jalisco”—David Washburn, principal trumpet), and La Kalva (“The Skull”—Wade Culbreath, principal timpanist), all pitted against the técnicos San Silver (“Saint Silver”—Margaret Batjer, Concertmaster), Volátigo (“Chameleon”—Sandy Hughes, principal flute), and Dominus (“The Master”—Robert Thies, piano).

Matching the choreographed, almost balletic action of a real Lucha Libre wrestling match, Contreras’ six combatants exhibit far more of nimble interaction than the sort of blunt confrontation that takes place between the two timpanists in their battle royal during the finale of Nielsen’s Symphony No. 4. The brief, pithy, themes associated with each of the rudos and técnicos thread in and out of Lucha Libre!’s constantly changing rhythmic and textural web—punctuated to mark the wrestling action by smacks from the slapstick and bass drum thumps.

Fanfares from the French horn announced the match’s start and its end, and in between Contreras maintained interest with his highly resourceful deployment of the LACO’s relatively small forces, amongst which much of the aural variety comes from the two percussionists, each playing a wide range of instruments. Lucha Libre! proved to be a tangy and flavorful occasional piece, much appreciated by the audience, though for this listener the referee might have called a halt a couple of minutes earlier.

|

| Antonin Dvořák in 1879, the year he first drafted his Violin Concerto. |

Perhaps in response to the work’s troubled gestation, involving extensive and repeated revisions under the influence of the great violinist Joseph Joachim, Dvořák unusually qualifies each movement’s initial tempo indication—Allegro, Adagio, Allegro giocoso—with ma non troppo (not too much).

If this injunction is emphasized it can turn the opening tutti, especially with a full-sized orchestra, into an over-portentous harbinger of drama that the nature of the work doesn’t really fulfill, but Maestro Martín and the relatively small LACO forces (strings 8-7-4-4-3) made it instead a crisp, even peremptory, call to action, to which guest soloist Gil Shaham responded with an easeful, lovingly-shaped opening solo.

|

| Gil Shaham. |

The first movement segued seamlessly as ever into an account of the Adagio that was as heartfelt and eloquent, with some exquisite duetting between soloist and woodwinds, as the furiant finale was ebullient and piquant. The whole performance, enthusiastically cheered, made one wonder, far from the first time, why this marvelous concerto isn’t performed as frequently as those Big Three Bs? For his encore, Shaham played the Gavotte en rondeau third movement from J. S. Bach’s Partita No. 3 in E major for solo violin, BWV 1006.

|

| Margaret Batjer pays tribute to Julie Gigante on the occasion of her retirement. |

|

| György Ligeti. |

Firstly, the slow-fast-slow-fast succession that comprises Ligeti’s slightly edgy and exploratory Concert Românesc (1951)—its highlight being the brooding call-and-response between one French horn in the orchestra and another up in the balcony in its Adagio ma non troppo third movement—formed a very different response to their source material than that of the blunt, plain-spoken brevity of Bartók’s six Romanian Folk Dances BB 76 (1915, orch 1917), all over and done in as many minutes.

And then both of these were in turn perfectly complemented by the smiling gaiety and indelible melodies of Kodály’s Dances of Galánta (1933), performed with all the requisite warmth and precision by Maestro Martín and his splendid players—an ideal finale with which to send the audience back out into that unfamiliarly chilly southern Californian night.

---ooo---

Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Ambassador Auditorium, Pasadena, Saturday, December 11, 2022, 7 p.m.

Photos: The performance: Brian Feinzimer; Gil Shaham: Chris Lee; Dvořák & Ligeti: Wikimedia Commons; Bartók & Kodály: filbert.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment